Seventeen hundred years ago at Nicaea, the first ecumenical council in history, the bishop of Rome at the time, Sylvester, was not present. He sent two of his presbyters, Vitus and Vincentius. And it is likely that due to precarious health his current successor, Francis, will not go either, to celebrate the great anniversary in ecumenical assembly with Protestant leaders and the heads of the Eastern Churches.

Seventeen hundred years ago at Nicaea, the first ecumenical council in history, the bishop of Rome at the time, Sylvester, was not present. He sent two of his presbyters, Vitus and Vincentius. And it is likely that due to precarious health his current successor, Francis, will not go either, to celebrate the great anniversary in ecumenical assembly with Protestant leaders and the heads of the Eastern Churches.

Yet Francis had said repeatedly that he wanted to be there, in Nicaea, setting aside at least for a moment the disputes over issues like “gender” theories, the marriage of priests, or women bishops, and bringing back to the center the capital question of the divinity of the Son of God made man in Jesus, for which reason and no other that Council of Nicaea was convened.

If only this shift in focus were to take place, Francis too would make his own that “overriding priority” which Benedict XVI had entrusted to the bishops of the whole world in his memorable letter of March 10, 2009: to reopen access to God to the men of little faith of our time, not “to just any god,” but “to that God whose face we recognize… in Jesus Christ, crucified and risen.” A priority that would also be a legacy entrusted by Francis to his successor.

It is not a given that such an unconventional “gospel” is capable today of penetrating into a world befogged with indifference to the ultimate questions. Nor was being heeded a given in those first centuries, when Christians were much more in the minority than they are today.

And yet the issue at stake at Nicaea had an impact back then that went far beyond the bishops and the theologians by profession.

In Milan, the bishop Ambrose occupied for days and nights, with thousands of the faithful, the basilica that Empress Justina wanted to assign to the faction defeated by the Council of Nicaea. The young Augustine was a witness to this and reported that in those days Ambrose wrote and set to music sacred hymns that, sung by the crowd, then entered the divine office that is still prayed today.

Gregory of Nyssa, a brilliant theologian from Cappadocia, depicted with biting irony the involvement of the common people in the dispute. If you ask a money changer about the value of a coin – he wrote – he will answer you with a dissertation on the begotten and the unbegotten; if you go to a baker, he will tell you that the Father is greater than the Son; if at the hot springs you ask if the bath is ready, you will get the reply that the Son arose from nothing.

Arius himself, the presbyter of Alexandria in Egypt whose theses were condemned at Nicaea, so thrilled the crowds that his theology even found expression in popular songs sung by sailors, millers, and wayfarers.

But what exactly were his theses? And how did the Council of Nicaea defeat them?

Eminent theologians and historians like Jean Daniélou and Henri-Irénée Marrou have written important pages in this regard, but an excellent reconstruction of that theological controversy and its historical-political context has also come out in the latest issue of the magazine “Il Regno,” with the byline of Fabio Ruggiero, a specialist on the first Christian centuries, and of Emanuela Prinzivalli, professor of the history of Christianity at the University of Rome “La Sapienza” and a first-rate scholar of the Fathers of the Church. The quotations are taken from their essay.

*

The conflict broke out in 323 in the Church of Alexandria, the primatial see of a vast territory, with two protagonists, the bishop Alexander and his presbyter named Arius. “Both maintained the divine origin and primordial divinity of the Son, but they distinguished themselves by their different understanding of the manner of the birth of the Son from the Father.”

According to the very words of Arius, in a letter to Bishop Eusebius of Nicomedia, his fellow pupil, these are his assertions that are most contested but that he does not deny in any way: “The Son has a beginning, while God is without beginning,” and “From nothing the Son is.”

Arius did not break, properly speaking, a previously formulated dogmatic unity in the Church of the time. This unity was still in development, and on the theme of the divine Trinity the most refined theology, but not shared by many, was up to then that of Origen.

Arius indeed came along in the wake of Origen, but with further developments that took to the extreme the subordination of the Son to the Father. And at first he was joined by Bishop Eusebius of Nicomedia, an ambitious rival of Alexander of Alexandria, each backed by a hefty contingent of bishops.

The conflict between those two important episcopal sees of the East was so heated that the emperor Constantine himself personally took action “to re-establish that religious peace which he considered absolutely necessary for the good order of the empire,” also applying to the Christian religion the prerogatives of the “pontifex maximus” traditionally proper to the emperor.

In his first letter to Alexander and Arius, Constantine laid on the bishop the greater responsibility for the conflict. But in a subsequent letter he changed his stance, after having an investigation carried out in Alexandria by Bishop Hosius of Cordova, his long-time trusted advisor.

So the emperor came to the decision to convene an ecumenical council, the first extended to the whole Church. As its location he chose Nicaea, today called Iznik, near Nicomedia, the imperial capital before Constantinople became so, and not far from the Bosphorus, to facilitate the arrival of bishops from remote shores.

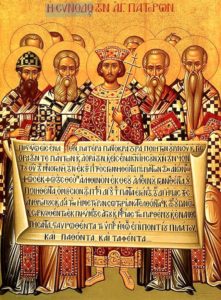

Constantine not only convened the council, but he presided over it and gave the opening speech, in the imperial hall of Nicaea. In the illustration above he is in the center, holding what would be the final document.

It was May 20, 325, and gathered around Constantine were more than 250 bishops, a hundred or so of them from Asia Minor, thirty from Syria and Phoenicia, fewer than twenty from Palestine and Egypt. Only six had arrived from the Latin West, including Hosius of Cordova, plus the two priests sent by Pope Sylvester. Arius was also present; he did not sit among the bishops, but would be consulted a number of times for clarifications on his doctrine.

“The account chronologically closest to the events is that of Bishop Eusebius of Caesarea,” Prinzivalli writes. Eusebius was a learned heir of Origen and his “Didaskaleion,” the refined theological school he founded in the land of Palestine. And he arrived in Nicaea with his own proposal for a “Symbol” of faith. Which, however, would not be the same as the one approved by the council at the end of its work.

Below are the opening paragraphs of the two texts, with the most relevant differences in italics.

SYMBOL OF EUSEBIUS OF CAESAREA

“We believe in one God, the Father Almighty, creator of all things visible and invisible. And in one Lord Jesus Christ, the Logos of God, God from God, light from light, life from life, only-begotten Son, firstborn of all creatures, begotten of the Father before all time, through whom all things were created.”

NICENE SYMBOL

“We believe in one God, the Father almighty, creator of all things visible and invisible. And in one Lord Jesus Christ, the Son of God, engendered as the only-begotten of the Father, that is, from the substance (‘usía’) of the Father, God from God, light from light, true God from true God, begotten, not created, consubstantial (‘homoúsios’) with the Father, through whom all things were created in heaven and on earth.”

Prinzivalli comments:

“Despite the similarities, we can consider it rather doubtful that the Symbol of Eusebius served as the basis for the Nicene. The Symbol presented by Eusebius is perfectly orthodox and would have brought everyone into agreement, but for this very reason it could not work, because at Nicaea one side necessarily had to be defeated. The agreement reached at Nicaea, with a compromise between quite divergent theologies, was imposed by Constantine, who, while never denying the Nicene Symbol, always considered it as merely instrumental to the re-establishment of religious peace”.

The Nicene Symbol is followed by this formula of condemnation:

“Those who say: ‘There was a time when He did not exist,’ or ‘He did not exist before having been begotten,’ or ‘He was created from nothing,’ or affirm that He is of another hypostasis or substance, or that the Son of God is either created or mutable or alterable, all of these the catholic and apostolic Church condemns.”

In the end, the consensus was very broad. The only ones to suffer condemnation and exile were Arius and two Libyan bishops, Theonas of Marmarica and Secundus of Ptolemais.

But the controversy was by no means resolved. Prinzivalli writes:

“Reaching religious consensus and peace requires, in fact, times that are not those of political imposition. The doctrinal clarification of the Cappadocian Fathers in the East and a second ecumenical council in Constantinople in 381 would be needed to obtain with the Nicene-Constantinopolitan Symbol a formulation truly accepted by the majority of the bishops, even if Arianism long continued to be the faith of the Germanic populations.”

The Nicene-Constantinopolitan Symbol, or “Creed,” is what is still proclaimed every Sunday in all the churches. But how many truly believe it?

—————

On the history and theology of the Council of Nicaea, today, February 27, is the opening of a major international conference at the Pontifical Gregorian University in Rome, to be followed in October by a second session in Germany, at the University of Münster. The first lecture, at the start of the proceedings, will be given by Professor Emanuela Prinzivalli. The schedule also included (before his hospitalization) a meeting with Pope Francis.

(Translated by Matthew Sherry: traduttore@hotmail.com)

————

Sandro Magister is past “vaticanista” of the Italian weekly L’Espresso.

The latest articles in English of his blog Settimo Cielo are on this page.

But the full archive of Settimo Cielo in English, from 2017 to today, is accessible.

As is the complete index of the blog www.chiesa, which preceded it.