On Friday, September 20, the popular movements will hold a symposium at the Vatican “to celebrate the tenth anniversary of their first meeting with Pope Francis.”

On Friday, September 20, the popular movements will hold a symposium at the Vatican “to celebrate the tenth anniversary of their first meeting with Pope Francis.”

Curiously, however, only “a message is planned” from the pope, in the announcement released by the dicastery for integral human development, headed by cardinal and Jesuit Michael Czerny. Nor is there any trace of the symposium in the events covered by the Holy See press office.

This downgrade is surprising when compared with the excessive emphasis Jorge Mario Bergoglio gave to his meetings with popular movements in the first years of his pontificate.

The first of these meetings was held in Rome ten years ago, in October 2014. The second in Bolivia, in Santa Cruz de la Sierra, in July 2015. The third again in Rome, in November 2016.

In all three, Francis stirred up the audience with long speeches, up to thirty pages each, outlining a sort of political manifesto. Applauding him, at the first two gatherings, was the “cocalero” president of Bolivia Evo Morales, highly criticized by the bishops of his country but plainly on familiar terms with the pope.

What the pope called “popular movements” were not his creation; they preexisted him. They were in part the heirs of the memorable anti-capitalist and anti-global rallies of the early 2000s, in Seattle and Porto Alegre. With which he associated the “cartoneros,” “cocaleros,” street vendors, amusement park workers, landless laborers, all the outcasts to whom he entrusted the future of humanity, thanks to their hoped-for rise to power “that may transcend the logical procedures of formal democracy” (just so, his words verbatim). The watchword issued by the pope was the triad “land, roof, work.” For all and right away.

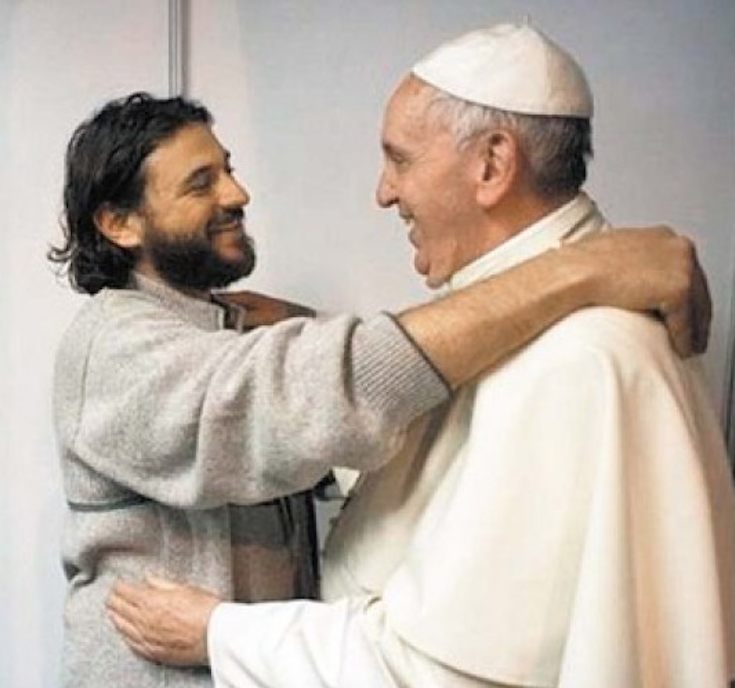

But then something started to break down, in Francis’s eyes. Due to friction above all with his fellow Argentine countryman Juan Grabois (in the photo), who was also the main organizer of the gatherings and had set the machine in motion since the first months of the pontificate, with a seminar at the Vatican on the “emergency of the excluded” held on December 5, 2013, with some of the future headliners of the meetings with popular movements.

At the symposium this September 20 at the Vatican, Grabois will again be one of the most visible protagonists, according to the announcement of the dicastery for integral human development, together with the Brazilian João Pedro Stédile, founder of the Movimento dos Trabalhadores Rurales Sem Terra, both still leading organizers of the popular movements. But it is precisely their presence, and above all that of the former, that induces Francis to stay away.

Grabois, 41, son of a past Peronist leader, had been close to Bergoglio since 2005, that is, since the then archbishop of Buenos Aires was at the head of the episcopal conference. After becoming pope, Francis appointed him as a consultant to the pontifical council for justice and peace, now absorbed into the dicastery for promoting integral human development. And at first he greatly appreciated Grabois’s ability to organize large gatherings with popular movements, forgiving him for his activity as one of the most combative “piquetero leaders,” with roadblocks, pickets of factories, squatting.

But after the third meeting, the one in 2016, something between the two began to go wrong.

A fourth meeting was scheduled for October 2017 in Caracas, but was canceled due to the disaster that Venezuela had been plunged into. Instead, the organization of meetings on a regional scale took shape.

In Grabois’s judgment, these meetings served as a virtuous counterpoint to the World Social Forums that were held every year following the first one in Porto Alegre, “which had degenerated into a series of rituals and tourist activities for militants.”

But at the Vatican they saw things differently. According to Vittorio Agnoletto, a member of the international council of the World Social Forum and consulted by the Holy See as an expert on the matter, the fear was that “a structuring of the popular movements by territorial networks would give rise to a series of ‘empty shells’ in competition with the World Social Forums.”

The fact is that at the first of the regional meetings of popular movements, held in Modesto, California, from January 16 to 19, 2017, Pope Francis appeared by videoconference to read a speech in line with his previous ones.

But at the second regional meeting, held in Cochabamba, Bolivia on June 20–21, the pope was a no-show.

And above all, Francis was infuriated when, in January 2018, on the eve of his trip to neighboring Chile, Grabois let loose with a withering verbal attack on Argentine president Mauricio Macri.

The trouble was that the Argentine media, in reporting the insults, said in chorus that Grabois was a great friend of the pope and that the pope thought as he did. Moreover, Grabois was leaving with five hundred militants of the popular movements to be in the front row at a Mass with Francis in Chile, against the “genocide” of the indigenous Mapuche people, for decades in conflict with the authorities in Santiago.

The Argentine episcopal conference felt obliged to respond to all of this with a tough statement of censure against those who exploit their friendship with the pope to make it seem that he thinks in the same way. Without naming names, but with a transparent allusion:

“Accompanying the popular movements in their struggle for land, housing, and jobs is a task that the Church has always performed and that the pope himself openly promotes, inviting us to lend our voices to the causes of the weakest and the most excluded. That does not imply in any way that he should be saddled with their positions and actions, whether these be correct or erroneous.”

But not even this severe reprimand appeased Francis. Who in 2020 again addressed the popular movements, but in his own personal way, with a brief open letter that did not make the slightest mention of the organizers of the previous meetings, much less of their resumption after the Covid pandemic.

The letter was dated and published April 12, Easter Sunday, without any reference to the risen Jesus and without any holiday greeting. In it, the pope called for a “universal basic wage” for everyone, and boldly complimented those women “who multiply loaves of bread in soup kitchens: two onions and a packet of rice make up a delicious stew for hundreds of children.”

And a few months later, in a handwritten letter dated December 1, 2020, sent to a group of his former Argentine students, made public in full by the recipients, the pope unloaded once and for all on the unfriended “Dr. Grabois”:

“Dr. Grabois, for years, has been a member of the dicastery for integral human development. Regarding what he supposedly says (that he is my friend, that he is in contact with me, etc.) I ask you a favor; for me it is an important one. I need copies of the statements in which he says this. Receiving them will be a great help to me.”

This because “in general, what is known there [in Argentina] is not what I say, but what they say that I say, and this on account of the media. Here the phenomenon of retelling plays a large role, e.g., that guy told me the other guy said this… and so with this method of communication, in which each one adds or takes something away, implausible results are achieved, like the story of Little Red Riding Hood ending up at a table where she and her grandmother eat a delicious stew made of wolf meat. So it goes with ‘retelling’.”

It is in part from this glimpse into his personal moods that one understands why Pope Francis gives an enormous number of interviews. Because he wants what he says to be heard directly from him, without intermediaries.

As for his innumerable handwritten letters, if in the future they are collected and published they will be a jam-packed mine for historians of this pontificate.

(Translated by Matthew Sherry: traduttore@hotmail.com)

————

Sandro Magister is past “vaticanista” of the Italian weekly L’Espresso.

The latest articles in English of his blog Settimo Cielo are on this page.

But the full archive of Settimo Cielo in English, from 2017 to today, is accessible.

As is the complete index of the blog www.chiesa, which preceded it.