At the Meeting that Communion and Liberation holds every late August in Rimini, this year with the general title “In desert places we will build with new bricks,” the standout is an exhibition dedicated to the martyrs of Algeria, also illustrated by a book soon to be released by Libreria Editrice Vaticana.

At the Meeting that Communion and Liberation holds every late August in Rimini, this year with the general title “In desert places we will build with new bricks,” the standout is an exhibition dedicated to the martyrs of Algeria, also illustrated by a book soon to be released by Libreria Editrice Vaticana.

Few people know that May 8, when Pope Leo was elected, was the liturgical memorial of these very martyrs, and that Numidia, modern-day Algeria, was the birthplace and home of Augustine, of whom Leo himself calls himself “son.”

And in fact, in the message he addressed to the organizers of the Meeting, signed by Cardinal Secretary of State Pietro Parolin, he wanted to highlight this closeness of his :

“The Holy Father has appreciated that one of the exhibitions characterizing this year’s Meeting is dedicated to the witness of the martyrs of Algeria. In them, the Church’s vocation to dwell in the desert in deep communion with all humanity, overcoming the walls of indifference that set religions and cultures against one another, in full imitation of the movement of the incarnation and giving of the Son of God. This way of presence and simplicity, of knowledge and of ‘dialogue of life,’ is the true path of mission. Not self-exhibition, in the contraposition of identities, but self-giving to the point of martyrdom of those who, day and night, in joy and amid tribulations, worship Jesus alone as Lord.”

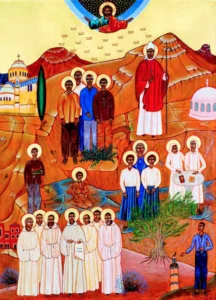

The martyrs of Algeria commemorated are the nineteen depicted in the icon reproduced here, painted by Sister Odile, a nun of the Little Sisters of Nazareth, all killed between 1994 and 1996 in the thick of the “black decade” of civil war that left 150,000 dead in Algeria.

Among them is a bishop, Pierre-Lucien Claverie, Dominican and “pied-noir,” that is, a French citizen born in Algeria, of the diocese of Oran, killed on August 1, 1996, together with his Muslim friend and driver Mohamed Bouchikhi, also depicted in the icon, the only one without the halo.

And then there are the most famous of the nineteen : the seven Trappist monks of the monastery of Tibhirine, in the Atlas Mountains, kidnapped with their prior Christian de Chergé on the night between March 26 and 27, 1996, and declared dead the following May 21 when their severed heads were found near Médéa. Their story was taken up in the film Of Gods and Men directed by Xavier Beauvois, which won an award at the 2010 Cannes festival and is now being presented again at the Rimini Meeting.

But remembrance and veneration also go to the four “white fathers” – the Missionaries of Africa founded in the 19th century by then bishop and cardinal of Algiers Charles Lavigerie – killed in Tizi Ouzou ; to the two white-robed missionary nuns of Our Lady of Apostles ; to the two Augustinian missionary nuns killed along with a Little Sister of Charles de Foucauld ; and finally to the Marist friar who curated a library and the nun of the Little Sisters of the Assumption killed with him, portrayed kneeling in the icon.

The exhibition and the book tell and illustrate the stories of each of these martyrs, beatified on December 8, 2018, in Algeria, at the shrine of Notre-Dame de Santa Cruz.

But all of their stories have some common features, which are important to highlight because they touch on vital issues regarding the presence of Christians in society.

Flourishing in the early centuries, the Christian presence in modern-day Algeria declined after the Muslim conquest and virtually disappeared from the 17th century. In the 19th century a revival of this presence was linked to French colonial rule, but even then with a different vision embodied by Charles de Foucauld and his hermitage among the Tuareg Muslims in Tamanrasset, in the heart of the Sahara Desert.

With the Algerian War of Independence, which ended in 1962, this “colonial bubble” burst and almost all the “pied-noirs” fled to France. The remaining Christians, all foreigners, formed a small and fragile community that recognized itself as a “guest” of the Algerian people, who were entirely Muslim. But they also wanted to share their lives and works with the population, in a dialogue that also touched on the respective faiths.

With different emphases. If on the one hand the prior of Tibhirine, Christian de Chergé, aimed for unity despite the differences between Christianity and Islam, toward a common invocation of the same God, on the other Bishop Claverie insisted instead on the specificity of the Christian faith : “There will be no encounter, dialogue, friendship unless on the basis of a recognized, accepted difference. Loving the other in his difference is the only possibility of loving him.”

But what put Christians to the test was the civil war that broke out in Algeria in 1990, between the post-colonial secular elite in power and the radical Muslims of the Islamic Salvation Front, who were victorious in the elections but prevented from governing.

In 1993 the rebels’ extremist wing, the Armed Islamic Group, issues an ultimatum to all “foreigners,” a word that for them is also synonymous with Christians. They must leave Algeria within a month, on pain of death. And as soon as the ultimatum expires the series of killings begins.

What to do ? Leave or stay ? For Christians, life is at stake. The Bishop of Algiers, Henri Teissier, asks the clergy this question, one by one. But everyone’s response is to stay. And the martyrdom of the nineteen is the fruit of this choice.

Two answers, in particular, have gone down history. From a monk and a bishop.

The monk was the prior of Tibhirine, Christian de Chergé. We have his spiritual testament, written in the days of the ultimatum and reproduced in its entirety in the book dedicated to the nineteen martyrs of Algeria. “One of the most beautiful pages ever written in the 1900s,” in the words of Cardinal Angelo Scola, the founder years ago of the Oasis Foundation for Islamic-Christian dialogue, which is promoting the Rimini exhibition together with Libreria Editrice Vaticana.

These are its opening lines :

“If it should happen one day — and it could be today — that I become a victim of the terrorism which now seems ready to engulf all the foreigners living in Algeria, I would like my community, my Church and my family to remember that my life was given to God and to this country.

“I ask them to accept the fact that the One Master of all life was not a stranger to this brutal departure. I would ask them to pray for me : for how could I be found worthy of such an offering ? I ask them to associate this death with so many other equally violent ones which are forgotten through indifference or anonymity.

“My life has no more value than any other. Nor any less value. In any case, it has not the innocence of childhood. I have lived long enough to know that I am an accomplice in the evil which seems to prevail so terribly in the world, even in the evil which might blindly strike me down. I should like, when the time comes, to have a moment of spiritual clarity which would allow me to beg forgiveness of God and of my fellow human beings, and at the same time forgive with all my heart the one who would strike me down.”

And these are the concluding lines, also addressed to his killer :

“For this life lost, totally mine and totally theirs, I thank God, who seems to have willed it entirely for the sake of that joy in everything and in spite of everything.

“In this ‘thank you,’ which is said for everything in my life from now on, I certainly include you, friends of yesterday and today, and you, my friends of this place, along with my mother and father, my sisters and brothers and their families, You are the hundredfold granted as was promised !

“And also you, my last-minute friend, who will not have known what you were doing : Yes, I want this thank you and this goodbye to be a ‘God-bless’ for you, too, because in God’s face I see yours. May we meet again as happy thieves in Paradise, if it please God, the Father of us both. Amen ! Inshallah!”

The other touching answer to the question “leave or stay?” is that of the bishop of Oran, Pierre-Lucien Claverie, in the homily he gave in Prouilhe, the founding place of the Dominican order, on June 23, 1996, five weeks before he was killed.

Here is the full text :

“Since the Algerian tragedy began, I’ve often been asked : ‘What are all of you doing down there ? Why do you stay ? Shake the dust off your sandals ! Go home!’

“Home… Where is home for us ? We are there because of this crucified Messiah. For no other reason, for no other person ! We have no interests to defend, no influence to maintain. We are not moved by some masochistic or suicidal perversion. We have no power, but we are there as if at the bedside of a friend, a sick brother, in silence, holding his hand, wiping his brow. Because of Jesus, because it is He who suffers, in that violence that spares no one, crucified anew in the flesh of thousands of innocents. Like Mary, his mother, like Saint John, we are there, at the foot of the Cross where Jesus dies, abandoned by his own, mocked by the crowd. For a Christian, isn’t it essential to be there, in the places of suffering, in the places of abandonment, of desolation ?

“Where should it be, the Church of Jesus which is itself the Body of Christ, if not first and foremost there ? I believe that it is dying precisely for the fact of not being close enough to the Cross of Jesus.

“As paradoxical as it may seem to you – and St. Paul demonstrates it clearly – the strength, vitality, hope, Christian fruitfulness, the fruitfulness of the Church come from there. Not from elsewhere, not in any other way. All, all the rest is nothing but smoke in the eyes, worldly illusion.

“The Church is mistaken and deceives the world when it presents itself as just one power among others, as an organization, even humanitarian, or as a spectacular evangelical movement. It may even shine, but it does not burn with the fire of God’s love, strong as death, says the Song of Songs.

Because it’s really about love here. Love first and foremost, and only love. A passion for which Jesus gave us a taste and showed us the way : there is no greater love than to lay down one’s life for one’s friends. To lay down one’s life. It’s not reserved for martyrs – or rather, perhaps we are all called to become martyrs, witnesses to the free gift of love, the free gift of our own lives.

This gift comes to us from the grace of God given in Jesus Christ. In every decision, in every act, to concretely give something of oneself : one’s time, one’s smile, one’s friendship, one’s expertise, one’s presence, even silent, even helpless, one’s attention, one’s material, moral, and spiritual support, one’s outstretched hand, without calculation, without reservations, without fear of losing oneself.”

At the head of the diocese of Oran today, which numbers 1,600 faithful of various nationalities out of over 10 million Algerian residents, is the Italian Davide Carraro of the Pontifical Institute for Foreign Missions. Meanwhile, at the monastery of Tibhirine – whose current five monks have moved to Midelt, Morocco, also in the Atlas Mountains – there is now a community of Chemin Neuf, which keeps the memory of the martyrs alive for visitors.

(Translated by Matthew Sherry : traduttore@hotmail.com)

— — — —

Sandro Magister is past “vaticanista” of the Italian weekly L’Espresso.

The latest articles in English of his blog Settimo Cielo are on this page.

But the full archive of Settimo Cielo in English, from 2017 to today, is accessible.

As is the complete index of the blog www.chiesa, which preceded it.