South of Gaza, in the heart of the Sinai Peninsula, stands a Christian monastery that in recent months has also been the subject of an international political and religious dispute over who is really in charge, a dispute at least provisionally resolved last October 16 with a “preliminary joint agreement” signed by the foreign ministers of Greece and Egypt, and three days later with the episcopal ordination of a new abbot.

South of Gaza, in the heart of the Sinai Peninsula, stands a Christian monastery that in recent months has also been the subject of an international political and religious dispute over who is really in charge, a dispute at least provisionally resolved last October 16 with a “preliminary joint agreement” signed by the foreign ministers of Greece and Egypt, and three days later with the episcopal ordination of a new abbot.

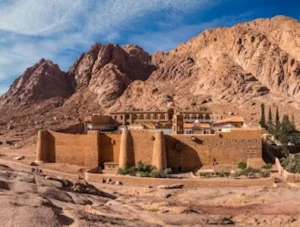

The monastery is dedicated to St. Catherine of Alexandria, whose body it houses, and sits at an altitude of 5,000 feet in the middle of the desert, on the site of the burning bush where God revealed himself to Moses and on the slopes of Jabal Musa, the mountain where the prophet and leader of the people of Israel on their journey to the promised land received the tablets of the law from God.

Founded in the 6th century by the Byzantine emperor Justinian, it is the oldest Christian monastery continuously inhabited to this day, thanks in part to the protection granted to it by Muhammad in 623 and later confirmed by the Ottoman sultans, as shown by a little mosque built there during the Fatimid era.

It houses the richest collection of Byzantine icons from before the destructive period of iconoclasm, and preserved one of the largest collections of ancient manuscripts in the world, including the Codex Sinaiticus from the first half of the 4th century, now in the British Museum, with the entire text of the New Testament and a large part of the Greek version of the Old.

The controversy was ignited by a ruling, on May 28 of this year, of the Egyptian court of appeals in Ismailia, which established that the monastery’s properties belong to Egypt and are subject to the supervision of the ministries of antiquities and the environment, without prejudice to the monks’ right to live there.

But at the same time another more religious dispute was splitting the monastic community in two. A dozen monks, out of 22 in all, had rebelled against the monastery’s abbot, Damianos, in office since 1974. And the main reason for the conflict was the monastery’s degree of autonomy from or subjection to the Greek Orthodox patriarchate of Jerusalem, headed since 2005 by Theophilos III.

Damianos, who was also archbishop of Sinai, Pharan, and Raitho and is Greek, as are all the members of the Jerusalem patriarchate’s hierarchy, asserted the autonomy of the monastery, “free, inviolable, and not subject to any patriarchal throne,” and in this he relied on the support of both the Greek Orthodox Church and the ecumenical patriarch of Constantinople, Bartholomew. While his opponents instead wanted to be under the patriarchate of Jerusalem.

Which, in a letter dated July 2 from Theophilos to Damianos, reaffirmed that it was this patriarchate, that of Jerusalem, that held “spiritual and canonical jurisdiction over the patriarchal and ‘stavropegial’[that is, directly subject – Ed.] monastery of Sinai” and that each of its abbots was also “bishop of the 24th episcopal see of the patriarchate.” This would also be confirmed by the fact that, by ancient tradition, it is the patriarch of Jerusalem who ordains as bishop each new abbot of St’s Catherine’s.

On the more strictly political terrain, the Greek government immediately began negotiations with the Egyptian government. And meanwhile, in Athens, a law was passed that countered the Ismailia ruling, establishing a new legal entity to “manage the monastery’s fixed and current assets,” with the members of the new entity’s board of directors appointed by the Greek minister of education and religious affairs.

This further ignited the conflict within the monastery, with the rebels now also hurling at Damianos the accusation of having collaborated with the Greek government in drafting the new law, without consulting the monks.

In Athens, in early August, a delegation from the patriarchate of Jerusalem waited in vain for three days for a meeting with Damianos, finally managing to meet not with him but only with some of his associates and a Greek government official.

The patriarch’s delegates then went to St. Catherine’s to meet with the monks aligned with them, to the irritation of the Greek government, which accused them of harming the ongoing negotiations with Egypt on the effects of the Ismailia ruling.

On August 26, upon Damianos’s return to Saint Catherine’s, unrest broke out. The rebellious monks were thrown out and the monastery gates were closed, while the ecumenical patriarchate of Constantinople on the one side and the patriarchate of Jerusalem on the other reaffirmed their respective opposing positions.

From Jerusalem, Damianos was summoned to give an account to the holy synod of the patriarchate, convened for September 8.

The abbot instead returned to Athens, where on September 8 – during the same hours in which the holy synod of the patriarchate in Jerusalem was deposing him as archbishop of Sinai, Pharan, and Raitho and calling for the election of a successor – he himself announced his resignation and the imminent appointment of a new abbot, notwithstanding that, to hear him tell it, the autonomy of the Sinai monastery had been “irrevocably defined with the seal of the ecumenical patriarch Gabriel IV in 1782,” with the patriarchate of Constantinople still remaining “the supreme pan-Orthodox arbiter.” All this with the agreement of the Greek government and the Church of Greece.

The fact is that the following Sunday, September 14, the monks of the monastery of St. Catherine unanimously elected the new abbot in the person of Symeon Papadopoulos, former archimandrite of the monastery of Alepochori in Greece, with the declared support of Church of Greece primate Ieronymos and Ecumenical Patriarch Bartholomew, whom he met with respectively on September 23 in Athens and on October 9 in Istanbul, as well as of the Greek government.

But the ordination of the new abbot as archbishop of Sinai, Pharan, and Raitho was once again, according to tradition, done by Patriarch Theophilos III of Jerusalem, on October 19 at the Basilica of the Holy Sepulchre, in a four-hour ceremony attended by representatives of other Orthodox Churches, including the patriarchate of Alexandria, and by two members of the Greek government, foreign minister Giorgos Gerapetritis and secretary general for religious affairs Giorgos Kalantzis, who had been the main architects of the reconciliation at St. Catherine’s Monastery. Neither in the homily of the new abbot and archbishop Symeon nor in the course of the ceremonies was there any further explicit reference to the patriarchate of Jerusalem’s claim to direct control of the monastery.

And in those same days, in mid-October, a “preliminary agreement” was also reached between the foreign ministers of Greece and Egypt on the ownership of St. Catherine’s monastery, implicitly recognized as Egypt’s but with “the character of the monastery guaranteed to remain unchanged in perpetuity,” with a ban on “any transformation of either the monastery or the rest of the places of worship” and the assurance that “the monks will remain.”

But still unresolved, at the bottom of everything, is the question of who in the Orthodox camp supervises St. Catherine’s monastery, with the opposing theses of the ecumenical patriarchate of Constantinople on the one side and of the patriarchate of Jerusalem on the other.

As proof of how strong this opposition is and how it goes well beyond the control of the Sinai monastery, a statement came on October 22 from Ecumenical Patriarch Bartholomew, who with the approach of the solemn celebration, on November 28 in Iznik, Turkey, of the 1700th anniversary of the Council of Nicaea, announced that, in addition to himself and Pope Leo XIV, the patriarchs of Alexandria and Antioch will participate in person, but not the patriarch of Jerusalem, the fifth of the so-called patriarchal “pentarchy” of the first millennium, as the latter did not respond to his written invitation.

Analyzing the reasons for this refusal, Peter Anderson, the Seattle scholar who is one of the world’s leading experts on Orthodoxy, emphasized the ties between the patriarch of Jerusalem and Patriarch Kirill of Moscow, accentuated by their common stance in support of Russia’s aggression against Ukraine.

Kirill cannot stand the reappraisal of the “pentarchy” of the first millennium, to which the latecoming patriarchate of Moscow could not belong, because it had not yet been established. And so he would not look favorably on the patriarch of Jerusalem’s visit to Izmir, accepting the invitation of Bartholomew, Kirill’s archrival in the Orthodox camp.

Meanwhile, every day St. Catherine’s draws streams of visitors – unaware of all this – from Sharm El Sheikh and other Red Sea vacation spots. Added to this is the project, launched in 2021 by the Egyptian government, to build in the environs of the monastery an international airport and a grandiose complex of luxury hotels and residences, called the “Great Transfiguration Project.”

The work is now stalled due to funding difficulties and opposition from international organizations like UNESCO and the Saint Catherine Foundation, under the patronage of King Charles of England.

And the war in Gaza has also contributed to putting the breaks on construction. Whose future, in the mountains of Sinai, bears a sinister resemblance to the much-vaunted postwar “Rivieras” along that stretch of coast.

(Translated by Matthew Sherry : traduttore@hotmail.com)

— — — —

Sandro Magister is past “vaticanista” of the Italian weekly L’Espresso.

The latest articles in English of his blog Settimo Cielo are on this page.

But the full archive of Settimo Cielo in English, from 2017 to today, is accessible.

As is the complete index of the blog www.chiesa, which preceded it.